I was having a conversation recently with someone who manages an independant engineering firm. He’s shared his new operating model: embedding individual developers directly inside his clients’ businesses. These engineers sit within the organization, spot inefficiencies, and spin up software to solve them. On the surface, it’s a smart play. But as he kept talking, something started to nag at me. His logic was sound, but incomplete. He was optimizing for production. What he wasn’t accounting for was the human layer. The part where a product has to land in someone’s life, not just function inside a business. That conversation unlocked something I’d been circling for a while.

As the cost of making software collapses, the advantage shifts away from building and toward translation: the act of turning a business need into an experience that fits how people already think, feel, and behave. When production is abundant, the scarce skill is making something people will actually adopt, trust, and keep. You can see the gap when speed becomes the goal.

A developer was brought into a startup I’m working with and asked to prototype the product experience, without my involvement. He was given the investor pitch, the business model, all the documents. Using AI, he turned it around fast. And what he produced was functional. It did what the business needed it to do. But it didn’t feel like anything.

The language was stiff and corporate, like a slide deck wearing the skin of an interface. Internal architecture language leaked straight through into the UI, with no context: entities, rails, flows, modules. It didn’t anticipate how a real person would interpret the experience, where they’d hesitate, or what would make them feel confident enough to proceed. It wasn’t bad engineering. It was missing translation. This is what I mean by the reframe.

If you hand someone a pencil and ask them to sell it, most people will start by describing the pencil: its features, its quality, its price. That’s product out. Translation starts the other way around. It begins with the customer’s world: what they’re trying to do, what keeps getting in the way, what they reject on sight.

If the customer struggles with imagination, the pencil stops being a drawing tool and becomes a tool for bringing an idea to life. The product doesn’t change, but the meaning does. Meaning is what makes someone try, return, and recommend. It creates space for something new. This same shift happened in physical production.

When globalization accelerated and China became the world’s factory, the economics of manufacturing changed. Efficiency went way up, costs went way down, and scalable production became widely accessible. Now, China can make almost anything. But being able to make something at scale is not the same as being able to sell it into a culture.

Breaking into Western retail markets requires more than manufacturing expertise. It requires an understanding of identity, aspiration, and psychology. It requires story, positioning, and taste. It requires knowing not just what the product is, but what it needs to mean to the person buying it. Software is heading toward the same reality.

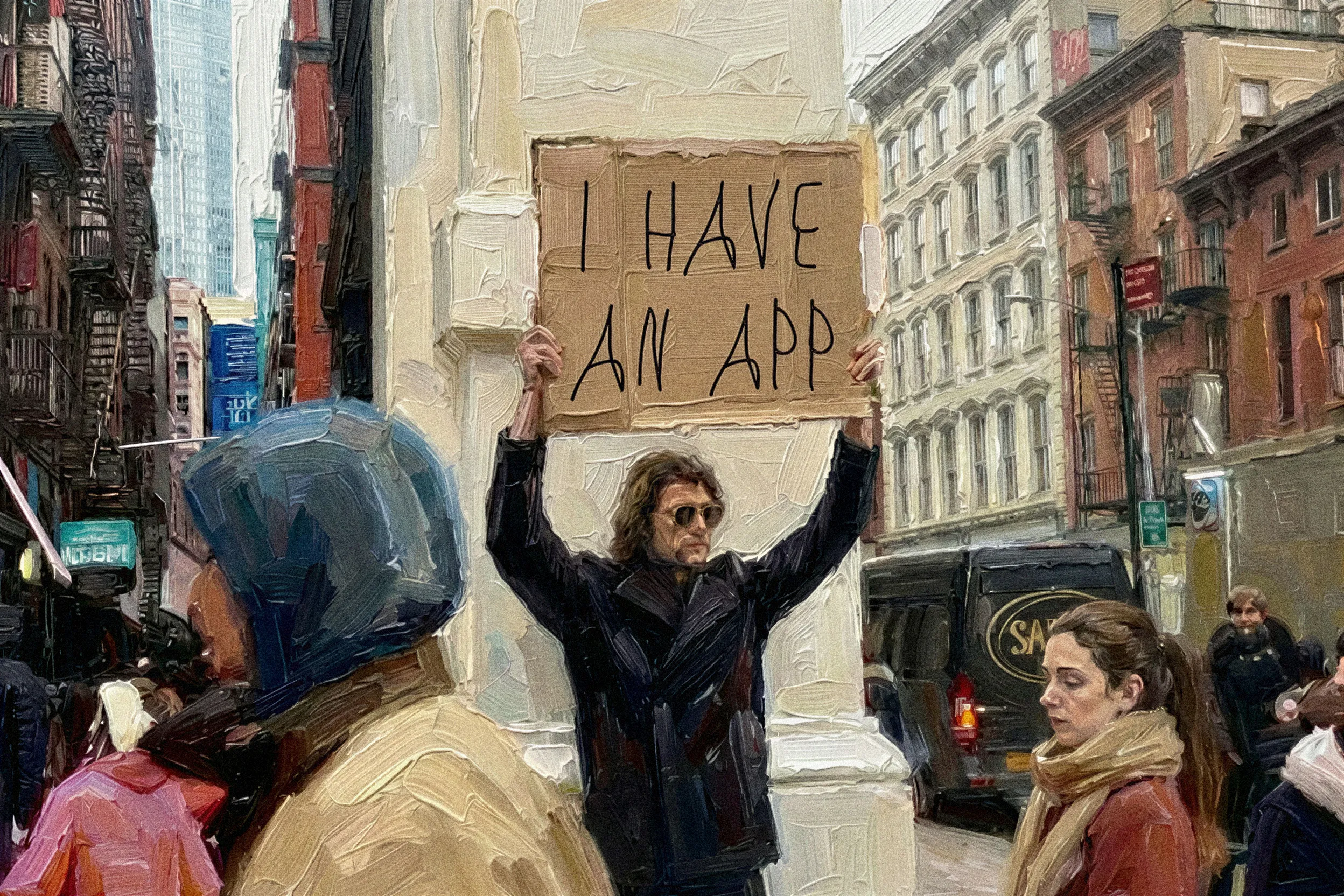

As AI drives down the cost and complexity of development, production stops being the bottleneck. Anyone with access to the right tools can build an app, prototype a platform, ship a feature. The barrier to making software keeps falling. Which means the market will keep filling with products that “work.”

When customers have to choose between twenty tools that do the same thing, function stops being enough. The decision becomes a tiebreaker between meaning, trust, and fit. Does this product align with how I see myself? Do I trust it? Would I recommend it to someone I respect?

That last question is where it gets interesting. Distribution today is social. Products don’t just spread because they’re useful. They spread because they make the person sharing them look credible, or because they offer relief someone wants to pass along. When a product mirrors something true about the user, an acute need, a lived frustration, an aspiration they recognize, recommending it becomes an act of self expression. It signals taste. It signals that they get it. Products without that quality can buy attention, but they can’t earn advocacy. This is where a widening gap becomes the whole game.

Engineering culture is trained to optimize for correctness, speed, and maintainability. Those instincts are essential, but they don’t automatically produce cultural fit. They don’t automatically produce resonance. And when production is no longer the differentiator, what’s left is the ability to close the distance between what can be built and what should be built. I know this because I lived a version of the same shift.

I spent years designing beautiful websites. Clean layouts, considered typography, thoughtful interactions. And then my clients would fill them with stock photography, lifeless copy, and creative that contradicted every decision I’d made. Over and over, the work I was proud of got buried under content I had no control over.

So I started moving upstream. I learned photography and creative direction so I could control the visual layer. That pulled me into brand expression, where I learned that creative direction has to align with something deeper: a brand’s identity. So I moved further upstream still, into brand strategy itself. And that’s where everything changed.

Working at the strategy level brought me closer to the core of my clients’ businesses. I stopped being someone who delivered work and became someone who shaped how the business showed up in the world. I became an extended member of the team, not a vendor. That intimacy built trust, and trust built long term relationships, the kind where you’re offered equity and recurring engagement because the business genuinely depends on the perspective you bring.

That experience taught me what this moment in software is about. When production becomes cheaper, what matters is coherence: holding the thread from intent to interface. Making sure the promise made in a pitch deck is the same one a user feels the first time they open the product. Not handing off between stages, but carrying the meaning through all of them.

The companies and individuals who will thrive in this next era aren’t the ones who can build the fastest. They’re the ones who can translate. The ones who can take a product and reframe it, not as a set of features, but as something that belongs in someone’s life.

There is a time tested process for creating meaningful software. AI can accelerate that process. But it should not be used to circumvent it.

Production has never been the hard part. Translation is. And it always will be.

.webp)